Resources for Practice and Study of Nichiren Buddhism

This page is created to support my practice and study and that of the communities in which I share my faith and courage. ~ Jenny

Chant with Us on ClubHouse

Join US in Nam Myoho Renge Kyo Club and Cozy Nook Chanting Nook

The GOAL is to Spread the Mystic Law who can deny anyone the opportunities to have Victory in this lifetime . . . . Certainly not me, walk with Courage & Roar like a Lion.

The GOAL is to Spread the Mystic Law who can deny anyone the opportunities to have Victory in this lifetime . . . . Certainly not me, walk with Courage & Roar like a Lion.

COZY CHANTING NOOK Website coming soon . . .

“A sword is useless in the hands of a coward. The mighty sword of the Lotus Sutra must be wielded by one courageous in faith. Then one will be as strong as a demon armed with an iron staff. I, Nichiren, have inscribed my life in sumi ink, so believe in the Gohonzon with your whole heart” (WND, 412).

The Liturgy of Nichiren Buddhism

Excerpts from the Lotus Sutra

Chapter 2: Expedient Means & Chapter 16: The Life Span of Thus Come One

| |||

Translation of Gongyo, the Liturgy of Nichiren Daishonin

https://sokanotes.blogspot.com/2008/10/translation-of-gongyo-liturgy-of.html

https://sokanotes.blogspot.com/2008/10/translation-of-gongyo-liturgy-of.html

Encouragement

|

Nichiren Daishonin states that the cherry, plum, peach, and damson each embody the ultimate truth just as they are, without undergoing any change (cf. OTT, 200).*1 This teaching provides us with a basic model for the way we should live our lives.

The cherry tree blossoms as a cherry tree, living to fulfill its own unique role. The same is true of the plum, peach, and damson trees. Each of us should do likewise. We each have a unique personality. We have a distinct nature and character, and our lives are each noble and respect worthy. That’s why we should always live with a solid self-identity, in a way that is true to ourselves. |

Each of us has a mission and a way of life that is ours alone. We don’t need to try to be like anyone else. The cherry tree has its own life and inherent causes for being a cherry. The plum, peach, and damson also each have their own inherent causes. And in the same way, from the viewpoint of Buddhism, we each have a mission we were born to carry out in this world, and each one of us has our own inherent causes to be who we are. Practicing the Mystic Law enables us to experience the joy of discovering this.

The most fundamental happiness in life is to bring forth our inner Buddhahood through the power of faith in the Mystic Law. The original text for study. . . .https://www.nichirenlibrary.org/en/ott/ImmeasurableMeanings/1#para-7

The most fundamental happiness in life is to bring forth our inner Buddhahood through the power of faith in the Mystic Law. The original text for study. . . .https://www.nichirenlibrary.org/en/ott/ImmeasurableMeanings/1#para-7

Basics, Concepts & Practice Resources

SGI Basics of Buddhism

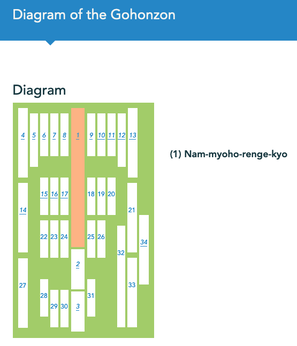

https://www.sgi-usa.org/basics-of-buddhism/ SGI Gongyo https://www.sgi-usa.org/study-resources/core-concepts/gongyo/ Key Concepts in Buddhism https://www.sokaglobal.org/practicing-buddhism/key-buddhist-concepts.html October 12th Anniversary of Gohonzon Inscription https://www.sgi-usa.org/study-resources/core-concepts/the-gohonzon/diagram-of-the-gohonzon/ |

Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo

In The Doctrine of Ichinen Sanzen (Ichinen sanzen homon), he writes:

When one chants Myoho-Renge-Kyo, the Buddhahood inherent in one’s life will be manifested. Those who have the opportunity to hear it will be able to eradicate their negative karma that has been accumulating for infinite asamkhya kalpas. Those (who hear Myoho-Renge-Kyo) and rejoice for even a single life-moment, will attain Buddhahood in their present form. Even if they hear it but do not believe in it, this constitutes the sowing of the seed of Buddhahood. Thus, the sown seed will become mature and enable one to attain Buddhahood without fail. (Gosho, p. 109)

In other words, Myoho-Renge-kyo is the seed that enables all people to attain enlightenment. Just by hearing it, we can eradicate great karmic offenses, and if we rejoice for even a single life-moment, we can immediately attain enlightenment. Moreover, when we sow the seed of Myoho-Renge-Kyo by means of shakubuku to others, even if they do not believe in it, the seed that is planted into their heart will eventually sprout and mature over time. They ultimately will attain enlightenment without fail. http://tbnsa.org/dharma/7547?lang=en

The Meaning of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo

The essence of Buddhism is the conviction that we have within us at each moment the ability to overcome any problem or difficulty that we may encounter in life; a capacity to transform any suffering. Our lives possess this power because they are inseparable from the fundamental law that underlies the workings of all life and the universe.

Nichiren, the 13th-century Buddhist monk upon whose teachings the Soka Gakkai is based, awakened to this law, or principle, and named it “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.” Through the Buddhist practice he developed, he provided a way for all people to activate it within their own lives and experience the joy that comes from being able to liberate oneself from suffering at the most fundamental level.

Shakyamuni, first awoke to this law out of a compassionate yearning to find the means to enable all people to be free of the inevitable pains of life. It is because of this that he is known as Buddha, or “Awakened One.” Discovering that the capacity to transform suffering was innate within his own life, he saw too that it is innate within all beings.

The record of Shakyamuni’s teachings to awaken others was captured for posterity in numerous Buddhist sutras. The culmination of these teachings is the Lotus Sutra. In Japanese, “Lotus Sutra” is rendered as Myoho-renge-kyo.

Over a thousand years after Shakyamuni, amidst the turbulence of 13th-century Japan, Nichiren similarly began a quest to recover the essence of Buddhism for the sake of the suffering masses. Awakening to the law of life himself, Nichiren was able to discern that this fundamental law is contained within Shakyamuni’s Lotus Sutra and that it is encapsulated and concisely expressed in the sutra’s title—Myoho-renge-kyo. Nichiren designated the title of the sutra as the name of the law and established the practice of reciting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo as a practical way for all people to focus their hearts and minds upon this law and manifest its transformative power in reality. Nam comes from the Sanskrit namas, meaning to devote or dedicate oneself.

Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is thus a vow, an expression of determination, to embrace and manifest our Buddha nature. It is a pledge to oneself to never yield to difficulties and to win over one’s suffering. At the same time, it is a vow to help others reveal this law in their own lives and achieve happiness.

The individual characters that make up Myoho-renge-kyo express key characteristics of this law. Myo can be translated as mystic or wonderful, and ho means law. This law is called mystic because it is difficult to comprehend. What exactly is it that is difficult to comprehend? It is the wonder of ordinary people, beset by delusion and suffering, awakening to the fundamental law in their own lives, bringing forth wisdom and compassion and realizing that they are inherently Buddhas able to solve their own problems and those of others. The Mystic Law transforms the life of anyone—even the unhappiest person, at any time and in any circumstances—into a life of supreme happiness.

Renge, meaning lotus blossom, is a metaphor that offers further insight into the qualities of this Mystic Law. The lotus flower is pure and fragrant, unsullied by the muddy water in which it grows. Similarly, the beauty and dignity of our humanity is brought forth amidst the sufferings of daily reality.

Further, unlike other plants, the lotus puts forth flowers and fruit at the same time. In most plants, the fruit develops after the flower has bloomed and the petals of the flower have fallen away. The fruit of the lotus plant, however, develops simultaneously with the flower, and when the flower opens, the fruit is there within it. This illustrates the principle of the simultaneity of cause and effect; we do not have to wait to become someone perfect in the future, we can bring forth the power of the Mystic Law from within our lives at any time.

The principle of the simultaneity of cause and effect clarifies that our lives are fundamentally equipped with the great life state of the Buddha and that the attainment of Buddhahood is possible by simply opening up and bringing forth this state. Sutras other than the Lotus Sutra taught that people could attain Buddhahood only by carrying out Buddhist practice over several lifetimes, acquiring the traits of the Buddha one by one. The Lotus Sutra overturns this idea, teaching that all the traits of the Buddha are present within our lives from the beginning.

Kyo literally means sutra and here indicates the Mystic Law likened to a lotus flower, the fundamental law that permeates life and the universe, the eternal truth. The Chinese character kyo also implies the idea of a “thread.” When a fabric is woven, first, the vertical threads are put in place. These represent the basic reality of life. They are the stable framework through which the horizontal threads are woven. These horizontal threads, representing the varied activities of our daily lives, make up the pattern of the fabric, imparting color and variation. The fabric of our lives is comprised of both a fundamental and enduring truth as well as the busy reality of our daily existence with its uniqueness and variety. A life that is only horizontal threads quickly unravels.

These are some of the ways in which the name “Myoho-renge-kyo” describes the Mystic Law, of which our lives are an expression. To chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is an act of faith in the Mystic Law and in the magnitude of life’s inherent possibilities. Throughout his writings, Nichiren emphasizes the primacy of faith. He writes, for instance: “The Lotus Sutra . . . says that one can ‘gain entrance through faith alone.’ . . . Thus faith is the basic requirement for entering the way of the Buddha.” The Mystic Law is the unlimited strength inherent in one’s life. To believe in the Mystic Law and chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is to have faith in one’s unlimited potential. It is not a mystical phrase that brings forth supernatural power, nor is Nam-myoho-renge-kyo an entity transcending ourselves that we rely upon. It is the principle that those who live normal lives and make consistent efforts will duly triumph.

To chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is to bring forth the pure and fundamental energy of life, honoring the dignity and possibility of our ordinary lives.

https://www.sokaglobal.org/resources/study-materials/buddhist-concepts/the-meaning-of-nam-myoho-renge-kyo.html

The essence of Buddhism is the conviction that we have within us at each moment the ability to overcome any problem or difficulty that we may encounter in life; a capacity to transform any suffering. Our lives possess this power because they are inseparable from the fundamental law that underlies the workings of all life and the universe.

Nichiren, the 13th-century Buddhist monk upon whose teachings the Soka Gakkai is based, awakened to this law, or principle, and named it “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.” Through the Buddhist practice he developed, he provided a way for all people to activate it within their own lives and experience the joy that comes from being able to liberate oneself from suffering at the most fundamental level.

Shakyamuni, first awoke to this law out of a compassionate yearning to find the means to enable all people to be free of the inevitable pains of life. It is because of this that he is known as Buddha, or “Awakened One.” Discovering that the capacity to transform suffering was innate within his own life, he saw too that it is innate within all beings.

The record of Shakyamuni’s teachings to awaken others was captured for posterity in numerous Buddhist sutras. The culmination of these teachings is the Lotus Sutra. In Japanese, “Lotus Sutra” is rendered as Myoho-renge-kyo.

Over a thousand years after Shakyamuni, amidst the turbulence of 13th-century Japan, Nichiren similarly began a quest to recover the essence of Buddhism for the sake of the suffering masses. Awakening to the law of life himself, Nichiren was able to discern that this fundamental law is contained within Shakyamuni’s Lotus Sutra and that it is encapsulated and concisely expressed in the sutra’s title—Myoho-renge-kyo. Nichiren designated the title of the sutra as the name of the law and established the practice of reciting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo as a practical way for all people to focus their hearts and minds upon this law and manifest its transformative power in reality. Nam comes from the Sanskrit namas, meaning to devote or dedicate oneself.

Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is thus a vow, an expression of determination, to embrace and manifest our Buddha nature. It is a pledge to oneself to never yield to difficulties and to win over one’s suffering. At the same time, it is a vow to help others reveal this law in their own lives and achieve happiness.

The individual characters that make up Myoho-renge-kyo express key characteristics of this law. Myo can be translated as mystic or wonderful, and ho means law. This law is called mystic because it is difficult to comprehend. What exactly is it that is difficult to comprehend? It is the wonder of ordinary people, beset by delusion and suffering, awakening to the fundamental law in their own lives, bringing forth wisdom and compassion and realizing that they are inherently Buddhas able to solve their own problems and those of others. The Mystic Law transforms the life of anyone—even the unhappiest person, at any time and in any circumstances—into a life of supreme happiness.

Renge, meaning lotus blossom, is a metaphor that offers further insight into the qualities of this Mystic Law. The lotus flower is pure and fragrant, unsullied by the muddy water in which it grows. Similarly, the beauty and dignity of our humanity is brought forth amidst the sufferings of daily reality.

Further, unlike other plants, the lotus puts forth flowers and fruit at the same time. In most plants, the fruit develops after the flower has bloomed and the petals of the flower have fallen away. The fruit of the lotus plant, however, develops simultaneously with the flower, and when the flower opens, the fruit is there within it. This illustrates the principle of the simultaneity of cause and effect; we do not have to wait to become someone perfect in the future, we can bring forth the power of the Mystic Law from within our lives at any time.

The principle of the simultaneity of cause and effect clarifies that our lives are fundamentally equipped with the great life state of the Buddha and that the attainment of Buddhahood is possible by simply opening up and bringing forth this state. Sutras other than the Lotus Sutra taught that people could attain Buddhahood only by carrying out Buddhist practice over several lifetimes, acquiring the traits of the Buddha one by one. The Lotus Sutra overturns this idea, teaching that all the traits of the Buddha are present within our lives from the beginning.

Kyo literally means sutra and here indicates the Mystic Law likened to a lotus flower, the fundamental law that permeates life and the universe, the eternal truth. The Chinese character kyo also implies the idea of a “thread.” When a fabric is woven, first, the vertical threads are put in place. These represent the basic reality of life. They are the stable framework through which the horizontal threads are woven. These horizontal threads, representing the varied activities of our daily lives, make up the pattern of the fabric, imparting color and variation. The fabric of our lives is comprised of both a fundamental and enduring truth as well as the busy reality of our daily existence with its uniqueness and variety. A life that is only horizontal threads quickly unravels.

These are some of the ways in which the name “Myoho-renge-kyo” describes the Mystic Law, of which our lives are an expression. To chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is an act of faith in the Mystic Law and in the magnitude of life’s inherent possibilities. Throughout his writings, Nichiren emphasizes the primacy of faith. He writes, for instance: “The Lotus Sutra . . . says that one can ‘gain entrance through faith alone.’ . . . Thus faith is the basic requirement for entering the way of the Buddha.” The Mystic Law is the unlimited strength inherent in one’s life. To believe in the Mystic Law and chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is to have faith in one’s unlimited potential. It is not a mystical phrase that brings forth supernatural power, nor is Nam-myoho-renge-kyo an entity transcending ourselves that we rely upon. It is the principle that those who live normal lives and make consistent efforts will duly triumph.

To chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is to bring forth the pure and fundamental energy of life, honoring the dignity and possibility of our ordinary lives.

https://www.sokaglobal.org/resources/study-materials/buddhist-concepts/the-meaning-of-nam-myoho-renge-kyo.html

The Immeasurable Meanings Sutra

Six important points

Point One, concerning the “Virtuous Practices” chapter of the Immeasurable Meanings Sutra

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: Regarding the three characters mu-ryō-gi, or “immeasurable meanings,” in the title of the sutra, if we consider them in terms of the three categories of theoretical teaching, essential teaching, and observation of the mind, then the first character, mu, represents the theoretical teaching. This is because it puts the theoretical perfection [that is, perfection in the theoretical truth] in the foreground and discusses that aspect of the meaning of the eternal and unchanging truth.

The theoretical teaching pertains to what is impermanent; it does not discuss that which is eternal and immutable. True, it states clearly that “these phenomena are part of an abiding Law, / that the characteristics of the world are constantly abiding” (Lotus Sutra, chapter two, Expedient Means). But this is to present the theoretical aspect of the eternal and immutable, not the actual aspect. It speaks of the characteristics of the theoretical eternal and immutable.

The word mu means kū, emptiness or non-substantiality. But this is not the mu of dammu that means that nothing remains after death. It is the mu that corresponds to the kū that is not separate [from temporary existence and the Middle Way]. This is the kū that p.200is spoken of in terms of the perfect teaching [or the unification of the three truths].

While the essential teaching deals with the actual aspect of the eternal and immutable, the Buddha eternally endowed with the three bodies, the theoretical teaching deals with impermanence. On the Protection of the Nation says, “The Buddha of the reward body, which exists depending on causes and conditions, represents provisional result obtained in a dream, while the Buddha eternally endowed with the three bodies represents the true Buddha from the time before enlightenment.”

Now Nichiren and his followers, who chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, are this true Buddha from the time before enlightenment who is eternally endowed with the three bodies.

Point Two, concerning the character ryō

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: The character ryō, “to measure” or “to estimate,” pertains to the essential teaching, because ryō has the meaning of “to weigh” and “to include.” The heart of the essential teaching is the exposition of the eternally endowed three bodies of the Buddha. This concept of the eternally endowed three bodies does not refer to the Buddha alone. It explains that all the ten thousand things of the universe are themselves revealed to have Buddha bodies of limitless joy. Therefore, while the theoretical teaching makes clear the theoretical perfection of the unchanging truth, the essential teaching takes over this explanation without change and deals with the eternally endowed three bodies present in each individual thing itself, setting forth the actual perfection of three thousand realms in a single moment of life as it is revealed in the essential teaching. When one comes to realize and see that each thing--the cherry, the plum, the peach, the damson—in its own entity, without undergoing any change, possesses the eternally endowed three bodies, then this is what is meant by the word ryō, “to include” or all-inclusive.

Now Nichiren and his followers, who chant p.201Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, are the original possessors of these eternally endowed three bodies.

Point Three, concerning the character gi

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: The character gi, or “meanings,” pertains to the observation of the mind. The reason is that, while words deal with the surface aspects [the text] of the teachings, meaning must be derived through observation of the mind. That is, the words that are preached in the sutras are referred to the realm of the mind in order to arrive at the meaning.

This is particularly true of the “immeasurable meanings” of the sutra, since the sutra discusses the “immeasurable meanings” that are born from a single Law. That which gives birth is gi, or “meaning” [that is, the “single Law”], and that which is given birth is muryō, that which is “immeasurable.” Hence this Immeasurable Meanings Sutra concerns both that which gives birth and that which is given birth. This, however, should not be taken as a statement of how these qualities of giving birth and being given birth apply to the relationship between the Lotus Sutra and the Immeasurable Meanings Sutra.

The Immeasurable Meanings Sutra states, “That which is without marks is devoid of marks and does not take on marks. Not taking on marks, being without marks, it is called the true mark [or the true aspect].” From this principle [the true aspect], the ten thousand things are derived. Their source is the true aspect, and hence this is a matter pertaining to the observation of the mind.

In this way, the three characters of the title, mu-ryō-gi, pertain to the theoretical teaching, the essential teaching, and the observation of the mind, respectively. And this expresses the transferred idea that this title of the sutra as it has just been explained and the title of the Lotus Sutra, Myoho-renge-kyo, form a single entity that is not dual in nature, and [of the three divisions of a sutra] the former serves as preparation and the latter as revelation.

p.202Point Four, concerning the character sho [in the phrase muryōgi-sho, “the origin of immeasurable meanings,” from the Lotus Sutra (chapter one, Introduction)]

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: This one character sho, “origin,” stands for the Lotus Sutra. The Tripitaka teaching and the connecting teaching are subsumed under the character mu of muryōgi; the specific teaching is subsumed under the character ryō; and the perfect teaching is subsumed under the character gi. Thus these four teachings of the sutras that preceded the Lotus Sutra are designated as that which was given birth, while this sutra, the Immeasurable Meanings Sutra, which acts as preparation for the Lotus Sutra, is designated as that which gives birth.

But now for the moment we use the character sho to indicate that which gives birth, and then the “immeasurable meanings” will be designated as that which was given birth. In this way we designate the sho, “the origin [of immeasurable meanings],” as it relates to the distinction between the true and the provisional teachings.

Point Five, concerning the phrase “the origin of immeasurable meanings”

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: The eight volumes of the Lotus Sutra correspond to the word “origin,” while the Immeasurable Meanings Sutra corresponds to the words “immeasurable meanings.”

The “immeasurable meanings” are the three truths, the threefold contemplation, the three bodies, the three vehicles, and the three categories of action. In the Lotus Sutra it is stated that “the Buddhas, utilizing the power of expedient means, apply distinctions to the one Buddha vehicle and preach as though it were three” (chapter two, Expedient Means). Thus the Immeasurable Meanings Sutra serves as preparation for the Lotus Sutra.

Here it is shown that the three truths viewed as separate from and independent of one another will not lead to the attainment of p.203the way; only the unification of the three truths will lead to such attainment. Hence the Immeasurable Meanings Sutra demolishes the former view by stating, “But in these more than forty years, I have not yet revealed the truth” (chapter two, Preaching the Law).

Point Six, concerning the phrase “the origin of immeasurable meanings”

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: The origin of immeasurable meanings represents the principle of three thousand realms in a single moment of life. Each of the Ten Worlds has its origin of meanings in immeasurable numbers. But these entities, just as they are, are none other than the one principle of the true aspect; this is explained [in the Lotus Sutra] as the true aspect of all phenomena. And this sutra serves as preparation for the Lotus Sutra, that is, preparation for the principle of three thousand realms in a single moment of life, and hence it is called “the origin of immeasurable meanings.”

The word “origin” corresponds to a single moment of life. The words “immeasurable meanings” correspond to the three thousand realms. The words that we utter morning and evening, as well as the two elements of environment and self, likewise have their origins of meanings in immeasurable numbers. And these are called Myoho-renge-kyo. Therefore this sutra serves as preparation or the opening sutra for the Lotus Sutra. https://www.nichirenlibrary.org/en/ott/ImmeasurableMeanings/1#para-7www.nichirenlibrary.org/en/ott/ImmeasurableMeanings/1#para-7

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: Regarding the three characters mu-ryō-gi, or “immeasurable meanings,” in the title of the sutra, if we consider them in terms of the three categories of theoretical teaching, essential teaching, and observation of the mind, then the first character, mu, represents the theoretical teaching. This is because it puts the theoretical perfection [that is, perfection in the theoretical truth] in the foreground and discusses that aspect of the meaning of the eternal and unchanging truth.

The theoretical teaching pertains to what is impermanent; it does not discuss that which is eternal and immutable. True, it states clearly that “these phenomena are part of an abiding Law, / that the characteristics of the world are constantly abiding” (Lotus Sutra, chapter two, Expedient Means). But this is to present the theoretical aspect of the eternal and immutable, not the actual aspect. It speaks of the characteristics of the theoretical eternal and immutable.

The word mu means kū, emptiness or non-substantiality. But this is not the mu of dammu that means that nothing remains after death. It is the mu that corresponds to the kū that is not separate [from temporary existence and the Middle Way]. This is the kū that p.200is spoken of in terms of the perfect teaching [or the unification of the three truths].

While the essential teaching deals with the actual aspect of the eternal and immutable, the Buddha eternally endowed with the three bodies, the theoretical teaching deals with impermanence. On the Protection of the Nation says, “The Buddha of the reward body, which exists depending on causes and conditions, represents provisional result obtained in a dream, while the Buddha eternally endowed with the three bodies represents the true Buddha from the time before enlightenment.”

Now Nichiren and his followers, who chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, are this true Buddha from the time before enlightenment who is eternally endowed with the three bodies.

Point Two, concerning the character ryō

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: The character ryō, “to measure” or “to estimate,” pertains to the essential teaching, because ryō has the meaning of “to weigh” and “to include.” The heart of the essential teaching is the exposition of the eternally endowed three bodies of the Buddha. This concept of the eternally endowed three bodies does not refer to the Buddha alone. It explains that all the ten thousand things of the universe are themselves revealed to have Buddha bodies of limitless joy. Therefore, while the theoretical teaching makes clear the theoretical perfection of the unchanging truth, the essential teaching takes over this explanation without change and deals with the eternally endowed three bodies present in each individual thing itself, setting forth the actual perfection of three thousand realms in a single moment of life as it is revealed in the essential teaching. When one comes to realize and see that each thing--the cherry, the plum, the peach, the damson—in its own entity, without undergoing any change, possesses the eternally endowed three bodies, then this is what is meant by the word ryō, “to include” or all-inclusive.

Now Nichiren and his followers, who chant p.201Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, are the original possessors of these eternally endowed three bodies.

Point Three, concerning the character gi

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: The character gi, or “meanings,” pertains to the observation of the mind. The reason is that, while words deal with the surface aspects [the text] of the teachings, meaning must be derived through observation of the mind. That is, the words that are preached in the sutras are referred to the realm of the mind in order to arrive at the meaning.

This is particularly true of the “immeasurable meanings” of the sutra, since the sutra discusses the “immeasurable meanings” that are born from a single Law. That which gives birth is gi, or “meaning” [that is, the “single Law”], and that which is given birth is muryō, that which is “immeasurable.” Hence this Immeasurable Meanings Sutra concerns both that which gives birth and that which is given birth. This, however, should not be taken as a statement of how these qualities of giving birth and being given birth apply to the relationship between the Lotus Sutra and the Immeasurable Meanings Sutra.

The Immeasurable Meanings Sutra states, “That which is without marks is devoid of marks and does not take on marks. Not taking on marks, being without marks, it is called the true mark [or the true aspect].” From this principle [the true aspect], the ten thousand things are derived. Their source is the true aspect, and hence this is a matter pertaining to the observation of the mind.

In this way, the three characters of the title, mu-ryō-gi, pertain to the theoretical teaching, the essential teaching, and the observation of the mind, respectively. And this expresses the transferred idea that this title of the sutra as it has just been explained and the title of the Lotus Sutra, Myoho-renge-kyo, form a single entity that is not dual in nature, and [of the three divisions of a sutra] the former serves as preparation and the latter as revelation.

p.202Point Four, concerning the character sho [in the phrase muryōgi-sho, “the origin of immeasurable meanings,” from the Lotus Sutra (chapter one, Introduction)]

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: This one character sho, “origin,” stands for the Lotus Sutra. The Tripitaka teaching and the connecting teaching are subsumed under the character mu of muryōgi; the specific teaching is subsumed under the character ryō; and the perfect teaching is subsumed under the character gi. Thus these four teachings of the sutras that preceded the Lotus Sutra are designated as that which was given birth, while this sutra, the Immeasurable Meanings Sutra, which acts as preparation for the Lotus Sutra, is designated as that which gives birth.

But now for the moment we use the character sho to indicate that which gives birth, and then the “immeasurable meanings” will be designated as that which was given birth. In this way we designate the sho, “the origin [of immeasurable meanings],” as it relates to the distinction between the true and the provisional teachings.

Point Five, concerning the phrase “the origin of immeasurable meanings”

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: The eight volumes of the Lotus Sutra correspond to the word “origin,” while the Immeasurable Meanings Sutra corresponds to the words “immeasurable meanings.”

The “immeasurable meanings” are the three truths, the threefold contemplation, the three bodies, the three vehicles, and the three categories of action. In the Lotus Sutra it is stated that “the Buddhas, utilizing the power of expedient means, apply distinctions to the one Buddha vehicle and preach as though it were three” (chapter two, Expedient Means). Thus the Immeasurable Meanings Sutra serves as preparation for the Lotus Sutra.

Here it is shown that the three truths viewed as separate from and independent of one another will not lead to the attainment of p.203the way; only the unification of the three truths will lead to such attainment. Hence the Immeasurable Meanings Sutra demolishes the former view by stating, “But in these more than forty years, I have not yet revealed the truth” (chapter two, Preaching the Law).

Point Six, concerning the phrase “the origin of immeasurable meanings”

The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings says: The origin of immeasurable meanings represents the principle of three thousand realms in a single moment of life. Each of the Ten Worlds has its origin of meanings in immeasurable numbers. But these entities, just as they are, are none other than the one principle of the true aspect; this is explained [in the Lotus Sutra] as the true aspect of all phenomena. And this sutra serves as preparation for the Lotus Sutra, that is, preparation for the principle of three thousand realms in a single moment of life, and hence it is called “the origin of immeasurable meanings.”

The word “origin” corresponds to a single moment of life. The words “immeasurable meanings” correspond to the three thousand realms. The words that we utter morning and evening, as well as the two elements of environment and self, likewise have their origins of meanings in immeasurable numbers. And these are called Myoho-renge-kyo. Therefore this sutra serves as preparation or the opening sutra for the Lotus Sutra. https://www.nichirenlibrary.org/en/ott/ImmeasurableMeanings/1#para-7www.nichirenlibrary.org/en/ott/ImmeasurableMeanings/1#para-7